There’s no doubt about it – the shoulder complex is one of the most commonly problematic areas on the body and can be frequently injured. But before we can talk about what can go wrong in this complex part of the body, we need to quickly review some anatomy and functionality.

The fist thing to note is that the shoulder complex is actually two articulations – the scapulothoracic ‘joint’ (really the muscular articulation of the scapula or shoulder blade on the chest) and the glenohumeral (GH) joint (the true shoulder joint). Let’s look first at the scapulothoracic joint and it’s anatomy.

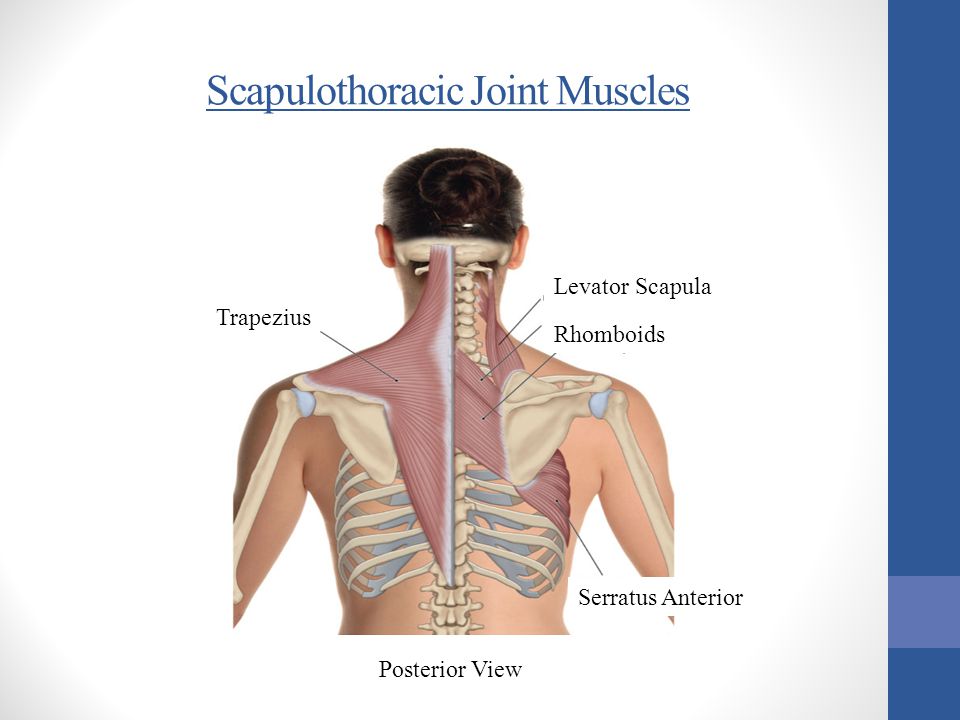

The Scapulothoracic Joint

So, as we can see above, the scapulothoracic joint is only connected to the skeleton via the clavicle. This creates joints at the sternum, the sternoclavicular joint (SC) and at the scapula (at a point called the acromion), the acromioclavicular joint (AC), allowing the clavicle to act as a strut for the shoulder complex and to provide some additional stability and force transmission to the skeleton.

Below we can see the muscles which act upon the scapulothoracic joint. Most of these are familiar to those of us who train in the gym, as these are the ‘shoulder muscles’ that are commonly trained in weight training, and also those that first pop into our mind when most of us think of ‘shoulder muscles’. It is important to note that these muscles, however, do not actually directly act on the shoulder joint – rather they control and stabilise the scapula.

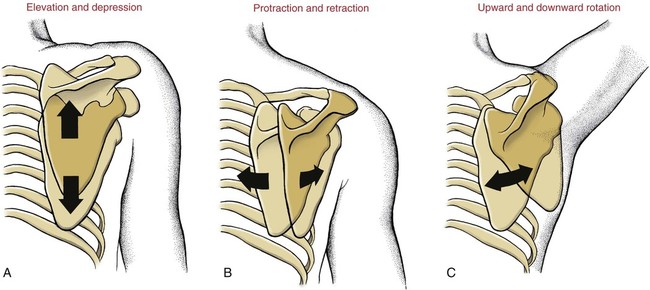

So, what is the purpose of having this joint? While there is a range of localised movements we can engage with the scapulothoracic joint, its most important function is to create and stabilise complex shoulder movements alongside the GH joint. We could think of this a method of actively extending the range of shoulder motion and increasing the power we can put through the shoulder joint through elevation, depression, protraction, retraction and upward/downward rotation.

You’ll notice that for these movements to occur, certain ranges of movement need to be available at both the AC and SC joints. Normal ranges of motion are as follows:

SC: Elevation: 48 degrees; Depression: 15 degrees; Protraction: 15-20 degrees; Retraction: 20-30 degrees

AC: Sufficient hinge and glide to allow for normal shoulder movement

The Glenohumeral (GH) Joint

Next we have the glenohumeral joint (GH), this is the ball and socket joint we all think of when we think of the shoulder. While it is technically a ball and socket joint, what makes the GH stand out is the shallowness of the socket which allows for a large range of motion. As the joint lacks bony stability, it relies upon dynamic stabilising in the form of the shoulder cuff muscles (the tendons of which also form the shoulder joint) and the tendons of biceps and triceps.

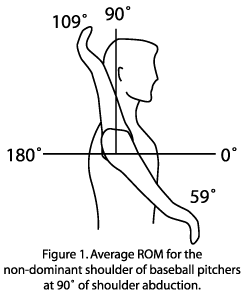

In addition to providing stability, the shoulder cuff muscles also produce a large proportion of the shoulder’s functional range of motion. The GH joint’s range of motion is illustrated below:

The Total Picture

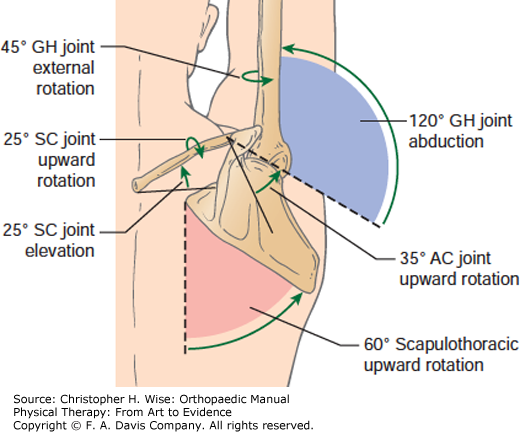

So, as we can see the shoulder complex is a complicated and dynamic area with many inter-related systems of movement and stability that must work together not only in strength, but in timing of their contraction while producing movement if we want to have a stable and healthy shoulder. The diagram below nicely illustrates how much each joint contributes to the simple task of a vertical press.

And of course, because the GH (the true shoulder joint) is a part of the scapula (which itself is capable of a large range of motion), how we stabilise the scapula has a tremendous impact on the GH joint’s mobility, stability and movement. Part D in the figure below illustrates this very nicely. We can see that a the scapula is protracted, retracted or winged, the orientation of the GH joint is altered significantly. This is an important concept for dealing with shoulder problems, as we will see.